Why Microservices?

See the trade-offs for microservices and how to create a platform experience for your developers that helps retain the agility gains of this new paradigm.

Speakers

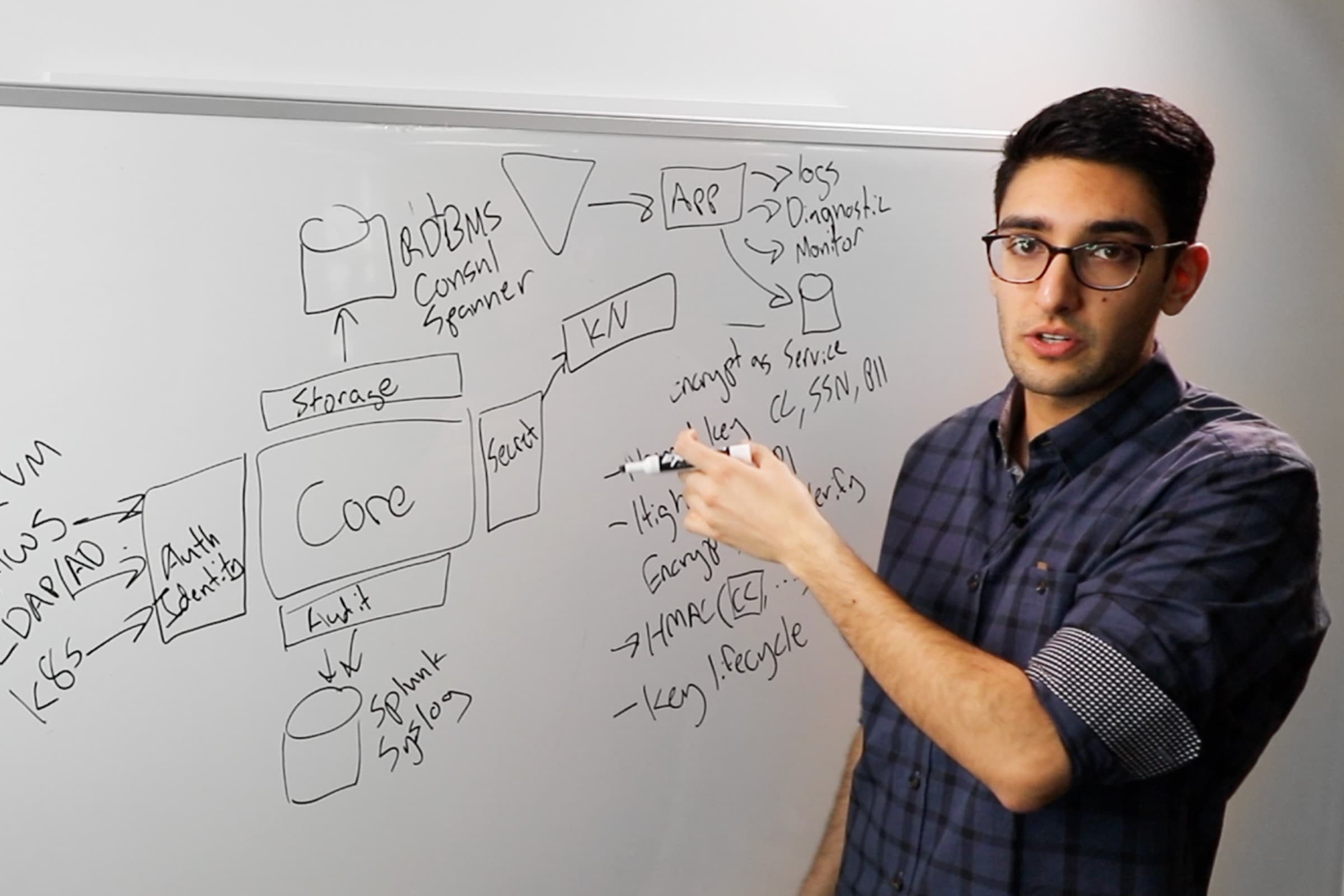

Armon DadgarCo-founder & CTO, HashiCorp

Armon DadgarCo-founder & CTO, HashiCorp

Microsevices are about helping individual teams working on an app being able to move quickly in parallel, rather than in a tightly-coupled manner that pushes releases out to quarterly timelines, rather than weekly timelines, which are more feasible in a microservices environment.

In this whiteboard video, HashiCorp co-founder and CTO Armon Dadgar explains the trade-offs and the things you need to consider in building a platform that shields developers from the shifts in complexity when you migrate from a monolith to microservices.

While microservices eliminate the human coordination costs of tightly-coupled monolithic releases, they introduce new operational challenges including service discovery, authentication and authorization between services, traffic management, and secrets management that didn't exist with in-memory function calls. The key to successful microservices adoption is establishing a strong platform team that handles all the underlying complexity—from infrastructure provisioning to networking to observability—so that application developers can focus solely on their source code and application logic rather than being burdened with distributed systems challenges.

Transcript

Hello. Today I want to spend a bit of time talking about "Why microservices?" Microservices is definitely a hot buzzword today, but I think it's useful to go one level deeper in terms of, "Why are we motivated to adopt a microservices architecture?" and, "What are the implications of adopting it?”

Oftentimes, we might not be adopting it for the right reasons, or we're not fully cognizant of all the implications that come with adopting a microservices architecture.

Starting high level, what are microservices? Why adopt them?

If you look at the way we historically developed applications, it had a bit more of a monolithic design pattern. If we had a large application that had multiple subsystems—it might be retail banking, for example, and you have your login, your balance view, transfers, bill pay—you might have had each of these built by a different team.

Each is a distinct application team, but ultimately they're building pieces of a common app. The challenge in this type of a setting is that each of the application teams had to coordinate tightly with one another. Team A couldn't do a release without team B, C, and D all being ready.

What you tend to see is a very tight release train, where all the teams have to coordinate on things such as "When do you cut the release candidate? When do you do betas? How do you do integration testing?"

You have almost a waterfall development timeline that comes with this. And the reason is, you have this tight coupling of the organization design. You have these 4 different app teams. They're tightly coupled into the application design. We're shipping a single app, but it spans multiple parts of the organization.

This is relatively simple when you only have 4 teams, but you can see how this explodes in complexity if you had, say, 10 different application teams working on a common codebase.

Part of the design of microservices, insofar as their technology, is that it's closely aligned to the organizational reality. Microservices are best to leverage when you look at this organizational reality and say, "What we really want to do is allow each of these application teams to work independently of one another."

We still have these different teams, but now we've split them out into unique services.

Each of these is now what we might call a microservice. We took the giant monolith. We decomposed it into its constituent parts.

But we did it in a way that's ideally aligned to the organization itself, because what we wanted to eliminate was the human cost of coordination, the cost of each of these app teams having to talk to one another constantly, having to figure out, "Can I cut a release? Because I have a bug in system A, but the codebase for B is not ready to go out," etc.

This is when I think microservices are best used. When you have this larger organization, you have many different teams that need to work together on a common codebase, and you can decompose such that each of them now has their own schedule.

So if A has a bug, they can deploy without needing to tightly coordinate with B, C, and D.

Making Tradeoffs

In reality, there's no free lunch. The human cost of coordinating between these teams on a release has to go somewhere. There still is a coordination cost.

We're just moving it around, and this is OK. We're making tradeoffs here. The tradeoff becomes: If A wants to be able to deploy at anytime—because they're fixing a bug or they're adding new features—if they have dependencies, if B and C depend on A, then they have to have an API contract. They can't just change their API because they're pushing out a bug fix, because they're going to break B and C.

Part of this now requires that you have a bit more discipline, a bit more rigor in terms of, How do you do things like API management? You have to manage versioning. You have to have some sort of a deprecation schedule or work at least closely with your downstreams to coordinate what might be a breaking change.

In general, when you're in a mode of, "I'm just fixing a bug; I'm not changing my API," that's great. You don't have to coordinate. You have total freedom. If I'm adding that new API, that's great. I don't have to tightly coordinate. As you break things, that's when you still need to have some of that coordination, or you need to have a well-known policy of how you do it.

You add new features, you have a deprecation period. B and C can update independently and move to the newer API, as an example.

At the same time, you also inherit a set of operational challenges when you go to microservices.

Here, by virtue of deploying this as a single monolithic application, if A needed to interact with D, this is an in-memory function call. We don't have to worry about networks. We don't have to worry about authentication or authorization, or all the challenges that come with becoming a distributed system.

The Discovery Challenge

As you move into this world, you inherit a bunch of challenges, part of them around things like, "How did these pieces discover and network to one another? So if A needs to communicate to D, how do we do that discovery?"

There's a whole set of service networking challenges that we need to look at. When we talk about service networking, the most basic initial challenge is, How do you do discovery?

A needs to find D somehow to be able to route to it. This is piece 1. Especially as we move to a more secure posture, we don't want any app to be able to call any app.

You have to start to think about things like, "How do I authenticate and authorize these different interactions?" A might be allowed to talk to D, but C should not be allowed to. I need to have some way to authenticate, to know, "Is my caller A? Is my caller B? Is my caller C?" That's the Authn challenge.

Then I have an authorization challenge where I define and say, "Which of these communications are allowed or disallowed?" And then as you get more sophisticated, you have things like a traffic management challenge.

The Traffic Management Challenge

When we talk about traffic management, you might get into scenarios where you're saying, "I'm running multiple copies of service A. Maybe I want to send 90% of my traffic to version 1 and 10% to version 2. I can do a canary or a blue-green test before going a 100% rollout to version 2."

As you get more sophisticated, these become your networking challenges that you didn't necessarily have, or at least not to the same degree when you had a monolithic challenge.

At the same time, closely related to some of these pieces, for example, AuthN and AuthZ, are things like secrets management, credential management.

If the way I'm authenticating A talking to D is I'm using a signed JSON Web Token, or I'm using a certificate that's signed to prove my identity, then I have a challenge of, How did these applications get those certificates, get those JWTs signed and verify transactions? That's where you typically have a secrets management problem as well.

The Secrets Management Problem

This might be something where you're using a solution like Vault. This might be something where you're using a solution like Consul that's providing the networking. And then, like I said, Vault might be providing this.

But coming back to these organizational challenges, the reason and the motivator to go to this kind of microservices architecture is, ultimately, I want to make these application teams more agile.

Microservices Shouldn't Be a Burden for Developers

What I don't want to do is burden them with all of this complexity of service networking and secrets management and application deployment, etc., because in some sense, that's going to take away from their original goal, which was to let them focus on the application, allow them to be more agile.

Often when you're moving to a microservices design, what's helpful to think about is, What's the platform experience?

What we really want, ideally, is that our developers are really focused on their source code, their application. And then, to the lightest degree possible, some additional metadata. This might live in the manifest that describes what their application needs: what regions it should run in, upstream dependencies, configuration, things like that.

Then, these should be the inputs to a platform layer. And the platform layer is what should shield them from the reality of how this thing operates. Everything below this line becomes an operational concern.

This is where you see teams that are successful with this. You have a strong notion that a platform team and a central operations team own everything up to this line, and then the developers can really focus on what matters to them, the actual app, the lifecycle, and operation of that.

And to the degree possible, we can mass these things. The platform teams have to deal with a bunch of these pieces of, How do we standardize things on infrastructure management and provisioning? How do we think about security and things like secrets management? How do we do networking? How's our application runtime look like? What's our container runtime platform, as an example? How do we do builds? How do we do observability?

There's a lot underneath this line, but I think if you're going to be successful, you want the platform to largely standardize these details. Put that below the line, make it an operational problem or a platform problem, and then let the developers operate at this higher level. And ultimately, it's coming back to understanding what's the organizational problem we're trying to solve.

The Organizational Challenge

It's that, as we scale, this cost of communication and coordination becomes increasingly expensive. That slows down our development velocity, versus if we can move and have tens, hundreds of these teams operating in parallel.

Not having to tightly coordinate, but instead having a set of norms around things like API management, and then allow them to operate on top of a platform that gives them that agility. Then these teams can go much, much faster. You could be making changes on a daily basis rather than on a quarterly basis.

Hopefully, this gave a little bit of a useful overview in terms of what microservices are and why. What's the organizational impact of adopting them, as well as what are some of the implications as we go down this model?

This post was updated August 2025.