Painless Password Rotation with HashiCorp Vault

Password management is a headache. Secrets management tools like Vault can alleviate this pain with password rotation automation.

For more in-depth tutorials and documentation for how to use HashiCorp Vault for password rotation, visit the Vault track on HashiCorp Learn.

Introduction: Nobody likes passwords. They are a pain to remember and complex rules and rotation requirements can actually make security worse.

Bad practices abound because password management is so cumbersome:

- Users copy annoying, hard-to-remember passwords onto sticky notes.

- Sometimes system passwords are stored in plain text on a wiki page or in a shared document.

- Credentials are often shared by multiple users, or the same username and password can be used to access multiple systems.

Password management is a thorn in the side of many sysadmins. Thankfully, Vault is a system that automates away most of the headaches associated with key and password rotation. Using built-in tools that you already have installed on your servers (Bash or Powershell), you can automatically generate secure passwords for Linux or Windows servers and store them safely in Vault.

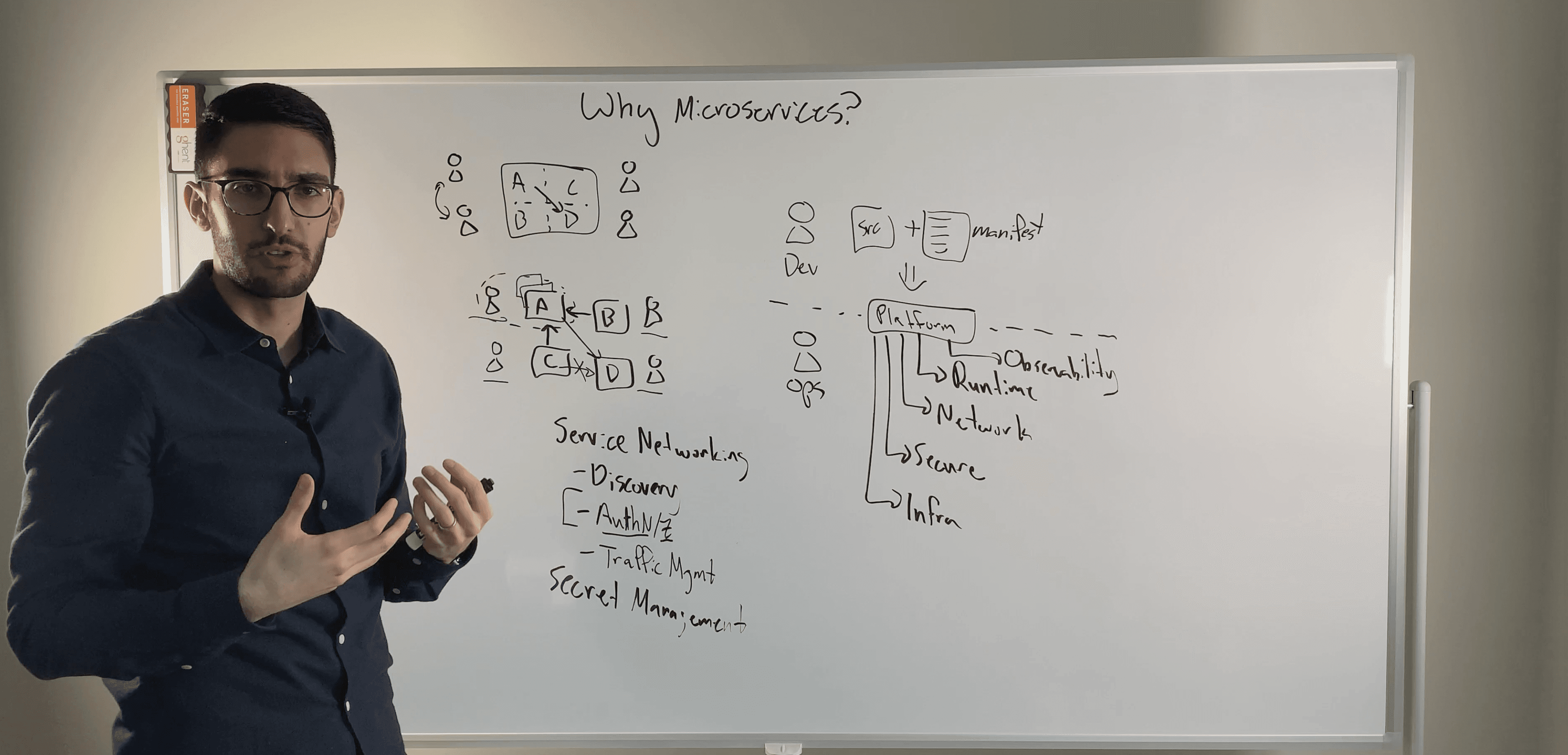

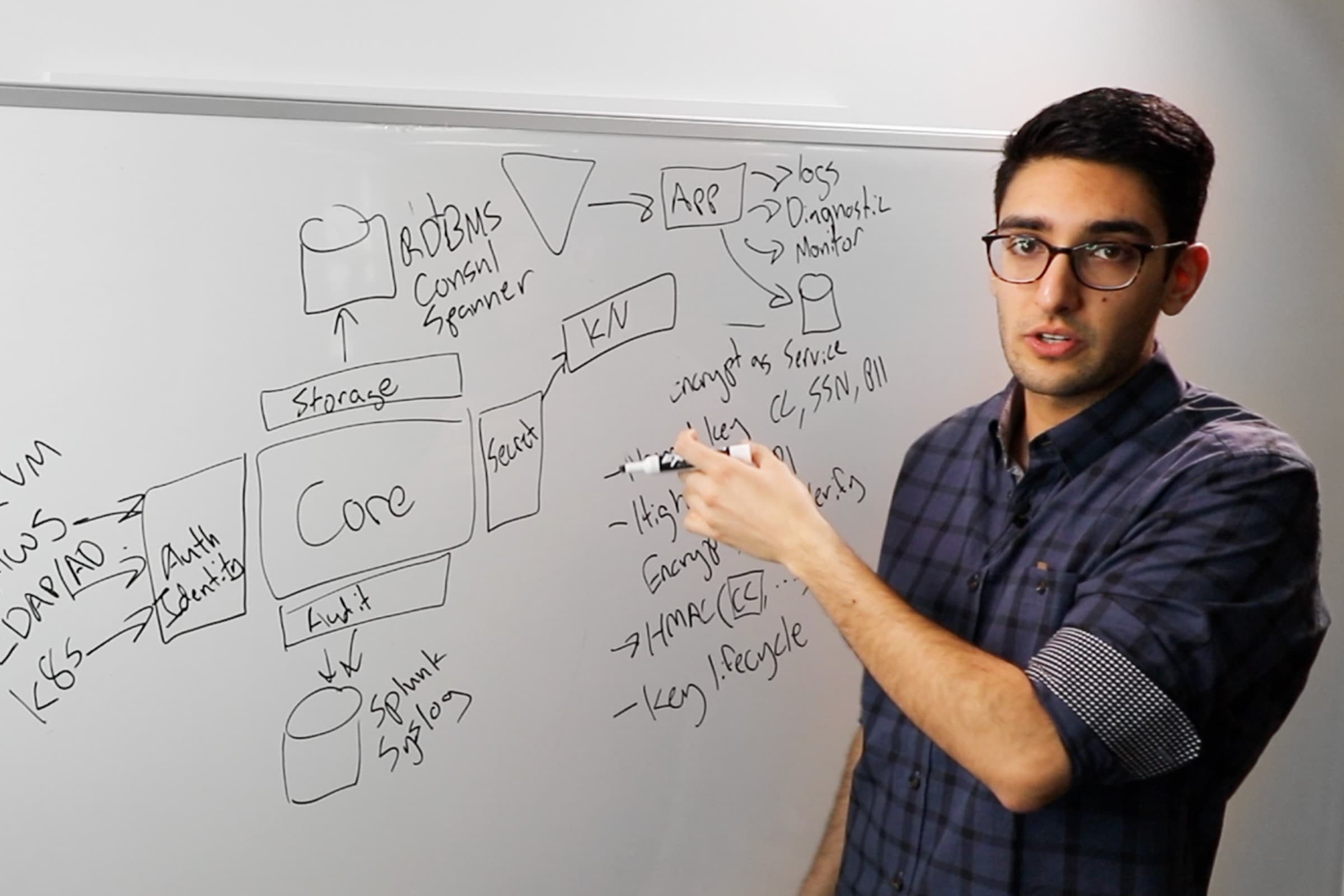

HashiCorp solutions engineer Sean Carolan demonstrates some of the ways you can clean up and automate your password management with Vault.

Speakers

Sean CarolanSolutions Engineer, HashiCorp

Sean CarolanSolutions Engineer, HashiCorp

Transcript

Good morning. My name is Sean Carolan, and I’m a former or recovering systems administrator. Today I’m a solutions engineer with HashiCorp. I like building things, so now I travel and help users get started with HashiCorp tools.

My first computer was a Commodore 64. Vintage, or heritage systems, right? This is a fairly recent photo, but that is a Commodore 64 in the photo. This is taken at the Living Computer Museum in Seattle. I highly recommend, if you’re ever in Seattle, go pay this place a visit. Do a pilgrimage to the Living Computer Museum. There’s nothing to make you feel old like seeing your childhood toy in a museum.

So, password rotation. Woo! Don’t all look so excited. Let’s be honest, all right? Nobody came to this talk because you like changing passwords, right? Did we all wake up this morning and go, “I’m going to change my password today.” No. So let’s look at an example.

The pain of changing passwords

Does anybody else do this? I do this. “I got 2 whole weeks. I don’t want to change my password. I can still get 2 more weeks use out of it, and after all it took me 3 weeks just to memorize the darn thing. You know what? I’m busy right now. Come back later. A day may come when I change this password, but today is not that day. Why can’t I just keep the password I have? I really like my password. OK. All right. We’re down to the wire. I’m going to do it this afternoon, I promise.” Nobody likes this, right? And this is just 1 password on 1 machine.

So, why do we participate in this crazy ritual every few months, and how did we get here? Most importantly, who can we blame? I did some research, and I tracked down the inventor of the modern computer password. So here he is. This dashing gentleman is Fernando Corbató. He’s one of the pioneers of time-sharing computer systems, and he led the team that developed the first compatible time-sharing system for mainframes. And he’s also known as the inventor of the modern computer password.

You see, back in those days, computers were these giant, hulking machines that filled entire rooms. These powerful machines were big and expensive to run. Users would write their programs on punch cards, and then submit the punch cards to the operators to run. So think about that next time you go to deploy your code, bringing a giant box of punch cards and dropping it on the sysadmin’s desk.

So these programs were put in a queue, and in the early days, they were run in serial, which means you had to wait days or hours for your program to run, and come back later to get the results. It wasn’t practical to have developers connected to the mainframe all the time, because most of the time, what are we doing? We’re typing, we’re thinking about things, we’re refactoring. We’re not actually using the CPU on the machine.

So Fernando and his team were tasked with solving this problem, and they came up with his concept of time-sharing. Multiple users could now connect to the same system and the idle time of users could be used as active time for another user. So finally you could have multiple users getting the most possible out of the mainframe.

Passwords: Problems from the get-go

So the password wasn’t originally invented for security. It was mainly just to keep the different researchers’ files separate back in 1961. So to quote Dr. Corbató, “The key problem was that we were setting up multiple terminals, which were to be used by multiple persons, but each person having his own private set of files, and putting a password on each individual user as a lock seemed like a very straightforward problem.”

And if Hollywood has taught us anything, it’s when the handsome scientist’s experiment starts, you know something’s going to go horribly wrong, right? And of course it did. Fernando, fortunately, is healthy, he’s still with us, and he didn’t turn into a fly, so things didn’t turn out quite that badly.

But less than a year after the password was invented, problems already started to come up. So we had the first instance of password theft in 1962, less than a year after this was invented. You see, these machines were very expensive to run, and so each user was allotted with 4 hours of compute time. And one of the other researchers on the project, Dr. Allan Scherr, he was frustrated with this 4-hour time limit. He knew, though, that there was an offline print function, where you could go in and submit a punch card and print files overnight and pick them up in the morning.

So on Friday evening, Dr. Scherr sent in a print job, then he showed up bright and early on Saturday morning and picked up the entire list of usernames and passwords for the system. Immediately the password list was shared with the other researchers on the team, and one of the other users immediately began to troll the administrator by posting messages under his system account. So we had the first internet troll in 1962.

And like that sci-fi movie plot, the brilliant scientist’s creation eventually came back to haunt him. Dr. Corbató said, “It’s become kind of a nightmare. I don’t think anybody could possibly remember all of the passwords.” So if the MIT PhD computer scientist thinks we have no hope, what hope is there for the rest of us, right?

Let’s turn the clock forward a little bit to the 1970s. While I was researching for this talk, I wanted to find the oldest machine I could log on to. And so this is Miss Piggy. Miss Piggy is a PDP-11 running in the same museum, the Living Computer Museum. Old school, right?

So this system and other systems in the 1970s used the same password file, but there were some minor improvements. So what we started to do is hash the passwords, which means we scramble them up, make it a little bit hard for someone to just run off with that list and start using other people’s passwords.

This is an example of a hashed password file. Little bit more difficult to get at, but the same basic concept is there. Every user has got some kind of password on the system, and they’re stored in this file here. So later on, we improve this what is called a salted hash, adding some random characters, and then hashing the password. But as time went by, computers got more powerful.

Does anyone remember when a 6-digit password was considered secure? Or 8? Right? Eight digits is no longer secure. A modern computer can crack through that fairly quickly. So computers keep getting more powerful and better at being able to guess passwords. And this has made it more and more difficult for the users, because now we have to remember longer and longer and more complex passwords.

How we set passwords now

So let’s choose a password. Let’s walk through a day in the life of a user. That user’s going to be me, and I’m going to choose a new password. This is my demon cat. I heard you could get internet points by putting a cat in your presentation, and she was having nothing of it. But this is Mochiko. So Mochiko is very cute and furry. Mochiko means rice flour. And I’m going to use my pet’s name for my password, because it’s easy to remember.

We’ll start with her short name. Easy to remember, but, unfortunately, very easy to crack. I ran a password-cracking tool against this password. Can you guess how long it took? Yeah, less than 2 minutes, so too short, too easy to guess. And that was on a very small instance that cost 7 cents an hour to run.

Let’s make it longer. Mochiko’s full name is a little bit better, but it’s still only 7 characters, and the security team says you need some numbers in there. Okay, we’ll tack a number on the end. Are we really fooling anyone here? You need some symbols, too; that’s part of our password requirements. All right, so we’ll swap a zero for an O and stick on an exclamation point. Now we’ve got this weird leetspeak mishmash of characters that hopefully we can remember.

Let’s make sure we never ever forget this password. You’ve never seen this in your workplace, have you? Why does this happen? We like to torture our users with these really weird complexity requirements for passwords. As it turns out, humans, on average, can reliably remember a group of 7 digits, about 6 letters or 5 words, plus or minus 2. They’ve done research on this. On average, people can remember about 7 digits, which coincidentally happens to be the length of a phone number, if you don’t include the area code.

Can anyone here remember 5 phone numbers? I see a couple of hands. Believe it or not, there was a time when many of us could recite a dozen phone numbers or more by heart. I can barely remember 3 phone numbers, and some of my friends don’t even know their own phone number anymore. Yet we’ve told our poor users, “You have to remember this string of 8 digits of random characters and letters and symbols.” What if instead we gave them a string of 4 or 5 words to learn?

So this is the xkcd comic illustrating this. On the top we have your classic numbers/letters/symbols-type password, which unfortunately happens to be pretty easy for a computer to guess. And in the comic he does some math, and estimates that it might take roughly 3 days if you just kept cracking away at this to break this password. On the bottom we have “correct horse battery staple.” “Correct horse battery staple.” You’re never going to forget that. And it turns out to be very hard for computers to guess this, because of the increased amount of entropy.

In other words, a really long password made of words is easier for humans to remember, harder for computers to guess. Sadly, these super-long passwords are not supported on many systems, because they don’t meet the complexity requirements.

So we turn to the password safe. Anyone use a password safe? Most of us, right? It’s a necessity in the modern world. So it’s either an app or a program, or maybe a user web browser that will let you securely store passwords. And your passwords end up stored on your laptop, or a smartphone, or in the cloud. Generally, you use a master password to unlock it and decrypt all of the other passwords.

Now, this is OK for personal use. But what happens if you have to manage hundreds of systems in the cloud or in the data center? This generally does not scale that well.

So we’ve looked at the history of password security. Let’s take a real short peek into the present and the future.

Automation is key to password nirvana

Here’s one possible solution to the problem of password management. What if you could hand out usernames and passwords that just automatically expired? Like an old spy movie or TV show, where the tape would self-destruct and burst into smoke and flames. Users and apps can simply check out new credentials when they need them, use them for a specific amount of time, and then the credentials automatically vanish when they expire. Sounds great, right?

I like the example of a ski resort. If you want to go skiing, you can buy a ski pass, and that pass has an expiration date, and it also has access levels. So maybe you get a beginner’s ski pass that gives you access to the bunny slope on the mountain, or you can get an all-season pass that lasts for a few months and lets you go on the black diamonds.

So dynamic credentials are very similar, and this is something HashiCorp Vault can do for you, either with your databases or in the cloud. It works the same way. You request those credential, you get them, you use them for a short period of time, and then they expire.

Sounds great, right? But I can hear you thinking, “But, Sean, I’m stuck with all these legacy machines that I have to manage, and I can’t do all this fancy dynamic stuff.”

Dealing with older systems

Let’s talk about the legacy systems. Does anyone have a machine like Miss Piggy on your network? Yeah? Wow, right on. So who here manages legacy systems for your organization? Please stand up. Don’t be shy. Stand up, stand up. Any machine that’s, say, over 5 years old, let’s consider that legacy. OK, we see a few. Let’s give these people a hand. Thank you. And that may be all the praise they got this entire year. So be nice to your sysadmins.

The reason these legacy systems are still around is because they still work. They were built too well, and they’re still serving some function. So what are we going to do about these systems? Some of my customers have started giving them new names.

A couple of weeks ago an IT director introduced me to his “classic” environment. So now they’re not legacy machines; they’re classic machines. But I think my favorite is the heritage collection. Perhaps it might not be surprising that this is a bank. So you could put that on your resume: “curator of heritage systems.”

If there’s one thing we know about these legacy systems, it’s that they’re not going away anytime soon. These dinosaurs have survived this long, and someone’s got to care for them. But the security team says, “You’ve got to rotate the root and admin passwords on these boxes every 90 days.” How are we going to tackle this challenge? So I set out to design a system that would automate your system password rotation and storage in a secure way. Here are the design requirements.

First of all, no external software. No one who’s managing that old Linux or Windows server wants to hear about Docker. Am I right? Why don’t you just put it in a container and sprinkle some DevOps on it and move it to the cloud? We want to keep it as simple as possible. Bash or PowerShell.

“We need a trusted source of entropy for password generation.” Now, obviously letting the human choose the password is not a good strategy, as you saw in the slide with my cat. We end up with a weird password that could probably be cracked pretty quickly.

The first revision of this tool used OpenSSL or PowerShell to generate passwords, but there are a couple of problems with this. We were not sure we can trust every machine to have the tools to do it right. And also, that is outside of our control. So what we’re going to do instead is use Vault itself to generate new passwords. We want each machine responsible for its own password rotation. You folks are busy. You came to a talk called “Painless Password Rotation,” so we want no manual steps at all. This should be something you can set and forget. The way we accomplish that is have each machine take care of itself.

Flexible password support

We want to be able to support different types of passwords, too. So the system should support both the long, complex strings of numbers and letters, and also the passphrase style of password. All passwords must be encrypted both in transit and at rest, and our servers should have write-only access. So in other words, we’ve formed a one-way door. When a new password is generated and stored in Vault, we don’t want that same machine to be able to go back and read the password again. It doesn’t need to.

We want to save n number of previous password versions. So what if I needed to go back and get the previous password, something that was set a week or a few days ago? Humans should be granted read-only access to these passwords by policy, and we want our passwords to be rotated automatically every x days, which is the whole point of this talk.

So those are our design requirements. Let’s go ahead and walk through what you can do to set this up in your own environment.

Step 1, or step 0, if you will, is get yourself a Vault. It’s easier than ever to set up HashiCorp Vault. You can download it for free. You can even unseal it using a cloud provider, so you can set up your HA-enabled Vault cluster. The second step is to install this password-generator plugin. This was created by Google’s Seth Vargo, real smart guy, and he created this password-generator plugin that you can use with Vault, and that way Vault becomes your password generator.

The next step is to enable a key-value store, or secrets engine. We’re going with version 2 of the KV store, because it supports versioning of our passwords.

And then we finally need some policies to determine how our machines can access Vault, and how our humans can access Vault. So on the top, we have the “rotate Linux” policy. We’re granting access to write new passwords into Vault, and we’re also granting access to the API endpoints that generate new passwords. Here’s the same thing for Windows. And all of this source code is online. I’ll give you the link at the end of the presentation.

Now we need a token. Here we’re generating a Vault token that our machine can use to run our password rotation script. We’re using a periodic token, which officially doesn’t have an expiration date, but it does require that the system check in on a regular basis. So this token has a 24-hour period, which means that of a machine doesn’t check in in 24 hours, that token is invalidated and you have to create a new one. This helps with cleanup. So if you decommission that legacy machine eventually, the token will expire very shortly thereafter.

And then the next step is to configure the scripts. So we have something for both Linux and Windows. Linux is a bash script, Windows is a PowerShell script. And there are 2 environment variables that you’re going to configure to make this work.

So you set the Vault address, the Vault token, and then run the scripts. How do these scripts work? I designed them to be all-in-one, and not have any external dependencies, so the first thing we do in our script is renew our token. We’re making a cURL command, or a cURL call with bash, or invoke-RestMethod with PowerShell. And we’re basically telling Vault, “Hey, I’d like to keep using this token. Please renew it for me.”

After the token’s been renewed, we go ahead and generate our new password. So again, we’re making an API call to Vault, hitting the passphrase or password endpoint. Vault is going to respond with a new password. Finally, we save that new password to the local system, but we need to do this in a safe way. We don’t want to cut off the branch that we’re sitting on and lock ourselves out of the system by changing the password and then failing to commit it to Vault.

So we do it the other way around. We first generate a secure password, we make sure it’s committed to Vault, and then we write it onto the local system. That way, if accidentally you wrote the password to Vault, but it didn’t make it onto the local system, you could still go back to the previous version, and you haven’t locked yourself out of your system.

The final step is to schedule the script, drop it into a Cron Job or a Windows scheduled task, and then forget about it.

A live demo

Let’s do a live demo. Here’s my legacy box. This password’s rotating every minute. You can see we’re using the long passphrase style of password here. And if I need to generate new passwords, I now have these API endpoints that I can use. So I can do a Vault write.

And we can do the same thing here with passwords. So if your requirements are that you have a long, complex password, you can do that as well, choosing the length. If you’re not a fan of symbols, you can limit the number of symbols as well.

So that’s our password source. And then on the client side, we have a Windows PowerShell script. We just rotated my personal password on this machine. So it will work with any username on this system. And if you try to rotate a password for a user that doesn’t exist, the script will fail.

That was the demo. So it was really short, and you can see why I had to put the history of computer passwords in this presentation, otherwise we would have been done in 2 minutes. I do have a couple more slides, though. Always there are the security folks in the room. “What if?” And we can’t get mad at them, because that’s their job, to say, “What if?” So I’ll walk through some of the what-ifs.

What if an attacker got their hands on a system token? What would they be able to do? Well, they’d be able to write arbitrary data onto your Vault instance, into the Linux or Windows path. They can’t overwrite the existing password, but they could continually just fill up your password store and roll off the older versions.

Another scenario, a little less likely, but they could write so much data that they fill your KV storage up entirely. Or as an alternate scenario, a DDoS or failure of your Vault cluster could, in theory, lock you out of all your systems. So there are some risks involved, and there are also some steps you can do to reduce those risks.

One would be to configure the Vault token so it could only be used during a very short time window. Maybe that’s 2 or 3 minutes when you run your scheduled task, that’s the only little window during the day that these scripts are allowed to run.

Another method you could use is to limit the length of the data that could be written into the key-value store. These are Vault Enterprise features.

A third one would be to use Vault in HA mode and use the DR, disaster recovery, feature, for emergencies. And that way, if the main Vault cluster went down, you can always fail over to the DR or replicated Vault cluster, and that way not be locked out of your systems. And then finally, you can monitor your Vault audit logs for any unusual activity on the systemcreds Linux or Windows endpoints.

Now, one final note: We do one other type of password rotation. If this is a challenge or a problem in your world, this is also built into Vault as of Vault 0.11. We can also rotate Active Directory passwords. This uses a lazy rotation. Passwords have a TTL, but they don’t get rotated until both the TTL have expired and the password is requested next. So it’s designed for high-load environments where you have multiple instances or services sharing the same system password.

You can download the code here. This will be posted online as well. Both the presentation and the scripts are available in this repo.

Thank you very much for attending. This has been “Painless Password Rotation with HashiCorp Vault.”